Blog

Beginner’s Guide to Healthcare Quality Improvement

Quality improvement in healthcare with an emphasis on the role of the electronic health record system. Readers should also find references to terminology and external resources to explore further.

Beginner’s Guide to Healthcare Quality Improvement

Overview

The Phrase Health team is committed to helping healthcare stakeholders in achieving the Triple Aim. This guide is meant to serve as a non-exhaustive resource for those interested in learning more about quality improvement in healthcare. There will be an emphasis on the electronic health record (EHR) system given its outsized impact on quality improvement and our company’s focus on analyzing interventions and their outcomes.

It is important to recognize that the field of quality improvement is not exclusive to healthcare. In fact, many of the principals around delivering quality outcomes and efficient processes were adopted from the manufacturing industry. Examples include Henry Ford and Toyota who recognized the need to deliver safe, reliable, and affordable products that would satisfy consumers.

What is Quality Improvement?

Quality improvement (QI) is the high-level framework for delivering systematic improvements to the production of a product or service. In healthcare, the focus is on maintaining a healthy society and delivering effective care to patients. Quality improvement can sometimes be used interchangeably with process improvement when the focus is on the intermediary steps of the delivery system.

DATA

In order to evaluate a process or output, it is important to study it using data. Only through data can an operator know the historical and current state of a process. This may seem obvious, but it’s not uncommon for projects to commence without a clear understanding of data availability, data accessibility, and data reliability. Perhaps the data that is needed to study an outcome is actually not quantified in any referenceable source (e.g. database, worksheets, etc.). Maybe it is available in a database, but the only analyst who can query the system has a six month backlog of other data requests. Consider a bug in the integration code of a wearable device company that causes only a fraction of data to be loaded.

While data can come from anywhere, the EHR has become integral to clinical workflows and, thus, serves as a rich source of data when embarking on a quality improvement initiative. These robust systems store clinical elements pertaining to the patient like a blood pressure level and blood test result. Additionally, it stores important information about the efficiency of processes that are involved in patient care. For example, it logs the adoption of clinical decision support tools like pop-up alerts and the results of these behavioral nudges. By joining the patient level data with this process data, you can see the potential for a robust quality improvement project.

VARIATION

Another foundational aspect of performing robust quality improvement is the identification of variation. The field shows that variation within a process is more likely to result in variation in the output. While this variation may intermittently lead to stellar outcomes, it may also result in dangerous ones as well. W. Edward Deming helped champion these concepts for the manufacturing industry, but these concepts can be mapped to healthcare as well.

While there are several ways to use the EHR to reduce variation, order sets are textbook examples. Order sets are a group or "menu" of orders that clinicians can place with a single click. Imagine working in the emergency department and a patient appears to have stroke-like symptoms. A single “Stroke Order Set” would include all of the necessary orders: CT scan, neurology consult, coagulation tests, among many others. Without an order set, Physician 1 may always order the CT scan, but forget to order the neurology consult and, as a result, delay time to deliver life-saving care. On the other hand, without an order set, Physician 2 may have been taught to get an X-Ray during their residency, so they weren’t aware that CT scan was the standard of care. In these examples, you can see how decreasing variation with an order set can lead to more reliable and effective care delivery that aligns with the best available practices.

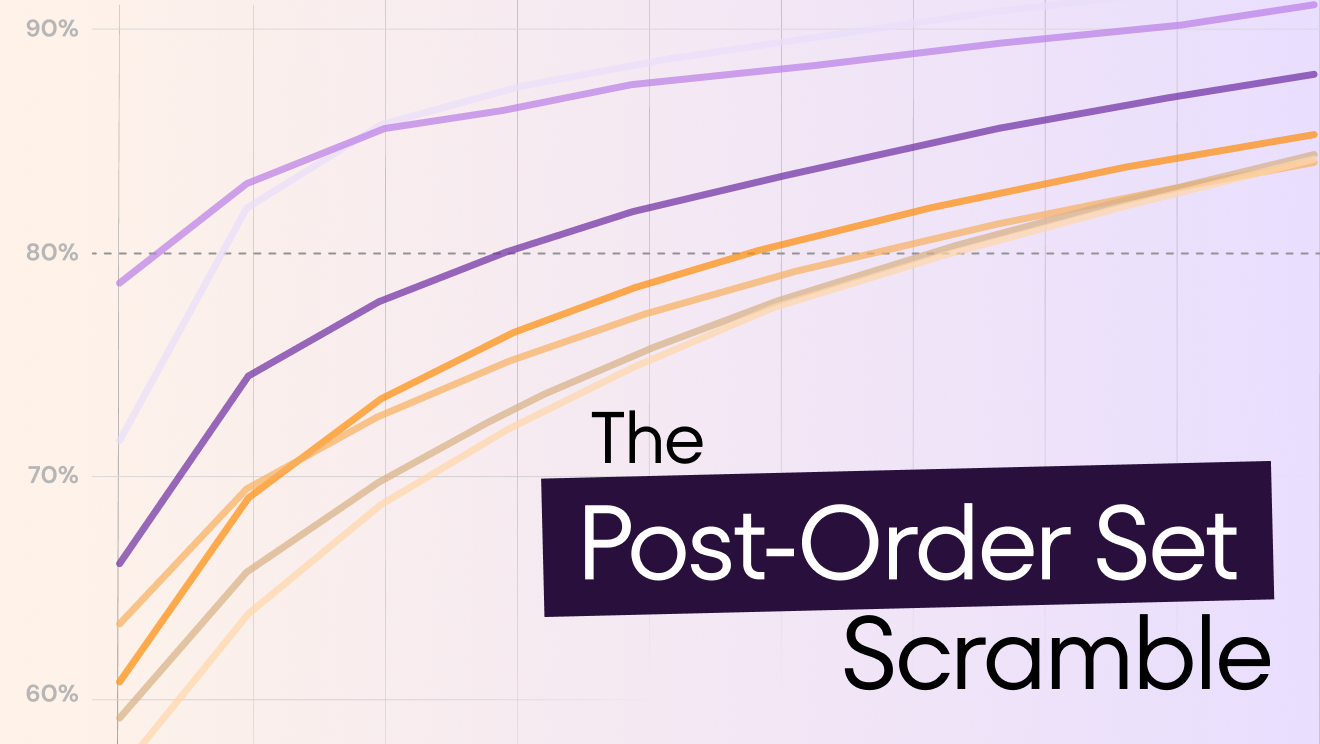

Variation with Random Ordering

"While there are several ways to use the EHR to reduce variation, order sets are textbook examples. Order sets are just that, a set of orders that clinicians can employ with a single click."

COST

One often thinks of “quality” as simply being produced well and, as a result, there is an association with it being expensive. In healthcare, quality improvement is frequently associated with cost containment as well. Healthcare spending in the United States, as of 2019, reached $3.8 trillion, which is 17.7% of the entire gross domestic product (GDP). In light of these large costs to our society, it is imperative that healthcare stakeholders include costs when they strive to improve healthcare.

The EHR is important for delivering and documenting patient care, but the mandatory clinical decision support tools it provides can also be a rich source of cost savings and unrealized revenue. For example, interventions like alerts and defaults in order sets can provide clinicians with information around more cost-efficient choices in medications.

Commonly Referenced Terms

This is a very limited list into some commonly referenced terminology that you may stumble across in your quality improvement explorations.

SIX DIMENSIONS OF HEALTHCARE QUALITY

The Institute of Medicine released a report in 2001 entitled “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” This landmark paper outlined six aims that helped define what it means to deliver healthcare quality. The six dimensions are:

- Safe: “avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them”

- Effective: “providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (avoiding underuse and overuse, respectively)”

- Patient-Centered: “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions”

- Timely: “reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care”

- Efficient: “avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy”

- Equitable: “providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status”

THE TRIPLE AIM

When looking at the Six Dimensions of Healthcare Quality, you’ll notice the focus on direct care delivery. The IHI recognized that the health of a population doesn’t exist only within the walls of a hospital room or doctor’s office. The Triple Aim incorporates the health of communities that could include important factors like healthy food accessibility and affordable public transportation. The three aims are typically presented as a triangle with the following points:

- Improving the patient experience of care

- Improving the health of populations

- Reducing the per capita cost of healthcare

Landmark Reports

The following represent commonly referenced reports that helped transform society’s perspective on healthcare quality and patient safety.

TO ERR IS HUMAN: BUILDING A SAFER HEALTH SYSTEM (1999)

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released this report and it helped open the eyes of many to the dangers of healthcare in the United States. The findings included the recognition that as many as 98,000 patients died every year as a result of medical errors. The analogy of a jumbo jet crashing each day was used to highlight the significance of these numbers. It’s no coincidence that the same year, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research changed its name to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

CROSSING THE QUALITY CHASM: A NEW HEALTH SYSTEM FOR THE 21ST CENTURY (2001)

The IOM followed up on “To Err is Human” two years later with a more comprehensive analysis of the state of healthcare in America. It is here that the authors outlined the Six Dimensions of Healthcare Quality through which stakeholders should try to improve the system. Importantly, the report recommends four levels when targeting the six dimensions:

- Patient experience

- Small unit of care delivery (“microsystem”)

- Organizations that encompass the microsystems

- Environment (e.g. legal, reimbursement, educational)

Expert Organizations

There are many organizations and institutions that are dedicated to healthcare quality improvement. However, these institutions play an integral role in the funding, education, and/or certification process.

AGENCY FOR HEALTHCARE RESEARCH AND QUALITY (AHRQ)

AHRQ is the principal federal agency that supports quality improvement research in the United States. Founded in 1989, AHRQ states its mission is “to produce evidence to make health care safer, higher quality, more accessible, equitable, and affordable, and to work within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and with other partners to make sure that the evidence is understood and used.” AHRQ had a total program funding level of $436 million in 2021. The largest portion of this budget, approximately $194 million, is dedicated to research on health costs, quality, and outcomes (HCQO).

INSTITUTE FOR HEALTHCARE IMPROVEMENT (IHI)

IHI is a non-profit organization that focuses on health quality. Founded in 1991, IHI states their mission is to “improve health and health care worldwide.” Unlike other organizations mentioned here, the IHI does not focus on the United States, but has regional efforts around the world. IHI’s website is a rich source for articles, methodologies, conference information, training programs, and more.

THE JOINT COMMISSION (TJC)

TJC is a non-profit organization that accredits healthcare organizations based on a set of national standards set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Founded in 1951, TJC evaluates the practices of healthcare systems programs and certifies eligibility to participate in CMS’ reimbursement programs based on these national standards. TJC currently accredits more than 22,000 organizations within the United States. TJC will visit health systems to do checks and audits of practices and processes. Importantly, TJC’s website is a rich source of information for quality improvement and patient safety.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR HEALTHCARE QUALITY (NAHQ)

NAHQ is a professional society dedicated to those interested in healthcare quality improvement. Founded in 1976, NAHQ’s mission is “to prepare a coordinated, competent workforce to lead and advance healthcare quality across the continuum of healthcare.” The organization sets a set of competencies required for healthcare quality specialists and administers a related Certified Professional in Healthcare Quality (CHPQ) exam. NAHQ additionally holds its annual NAHQ NEXT conference alongside other events and educational opportunities.

Journals and Publications

It’s important to recognize that there are great pieces published in a variety of settings. The following is a selection of some publications that principally focus on quality improvement and patient safety.

BMJ QUALITY & SAFETY

A peer-reviewed journal within the umbrella of the BMJ Publishing Group. The monthly publication seeks original material on “the science of improvement, debate, and new thinking on improving the quality of healthcare.”

JOURNAL FOR HEALTHCARE QUALITY

The official peer-reviewed journal of the National Association for Healthcare Quality is published every two months. The journal states it is a “professional forum that continuously advances healthcare quality practice in diverse and changing environments, and is the first choice for creative and scientific solutions in the pursuit of healthcare quality.”

THE JOINT COMMISSION JOURNAL ON QUALITY AND PATIENT SAFETY

The official peer-reviewed journal of The Joint Commission. The monthly publication encourages submissions on the “development, adaptation, and/or implementation of innovative thinking, strategies, and practices in improving quality and safety in health care.”

PHRASE'S EXPERTISE

Improved Adherence to Hepatitis C Screening Guidelines →

Responding to COVID-19: Reducing Documentation →

References

1. “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.” National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25057539/.

2. Monsen CB, Liao JM, Gaster B, Flynn KJ, Payne TH. “The Effect of Medication Cost Transparency Alerts on Prescriber Behavior.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31321427/.

3. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.” National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25077248/.

Quality improvement in healthcare with an emphasis on the role of the electronic health record system. Readers should also find references to terminology and external resources to explore further.

Written by

Dr. Marc Tobias

Jul 21, 2021

Written by

Dr. Marc Tobias

Jul 21, 2021

Overview

The Phrase Health team is committed to helping healthcare stakeholders in achieving the Triple Aim. This guide is meant to serve as a non-exhaustive resource for those interested in learning more about quality improvement in healthcare. There will be an emphasis on the electronic health record (EHR) system given its outsized impact on quality improvement and our company’s focus on analyzing interventions and their outcomes.

It is important to recognize that the field of quality improvement is not exclusive to healthcare. In fact, many of the principals around delivering quality outcomes and efficient processes were adopted from the manufacturing industry. Examples include Henry Ford and Toyota who recognized the need to deliver safe, reliable, and affordable products that would satisfy consumers.

What is Quality Improvement?

Quality improvement (QI) is the high-level framework for delivering systematic improvements to the production of a product or service. In healthcare, the focus is on maintaining a healthy society and delivering effective care to patients. Quality improvement can sometimes be used interchangeably with process improvement when the focus is on the intermediary steps of the delivery system.

DATA

In order to evaluate a process or output, it is important to study it using data. Only through data can an operator know the historical and current state of a process. This may seem obvious, but it’s not uncommon for projects to commence without a clear understanding of data availability, data accessibility, and data reliability. Perhaps the data that is needed to study an outcome is actually not quantified in any referenceable source (e.g. database, worksheets, etc.). Maybe it is available in a database, but the only analyst who can query the system has a six month backlog of other data requests. Consider a bug in the integration code of a wearable device company that causes only a fraction of data to be loaded.

While data can come from anywhere, the EHR has become integral to clinical workflows and, thus, serves as a rich source of data when embarking on a quality improvement initiative. These robust systems store clinical elements pertaining to the patient like a blood pressure level and blood test result. Additionally, it stores important information about the efficiency of processes that are involved in patient care. For example, it logs the adoption of clinical decision support tools like pop-up alerts and the results of these behavioral nudges. By joining the patient level data with this process data, you can see the potential for a robust quality improvement project.

VARIATION

Another foundational aspect of performing robust quality improvement is the identification of variation. The field shows that variation within a process is more likely to result in variation in the output. While this variation may intermittently lead to stellar outcomes, it may also result in dangerous ones as well. W. Edward Deming helped champion these concepts for the manufacturing industry, but these concepts can be mapped to healthcare as well.

While there are several ways to use the EHR to reduce variation, order sets are textbook examples. Order sets are a group or "menu" of orders that clinicians can place with a single click. Imagine working in the emergency department and a patient appears to have stroke-like symptoms. A single “Stroke Order Set” would include all of the necessary orders: CT scan, neurology consult, coagulation tests, among many others. Without an order set, Physician 1 may always order the CT scan, but forget to order the neurology consult and, as a result, delay time to deliver life-saving care. On the other hand, without an order set, Physician 2 may have been taught to get an X-Ray during their residency, so they weren’t aware that CT scan was the standard of care. In these examples, you can see how decreasing variation with an order set can lead to more reliable and effective care delivery that aligns with the best available practices.

Variation with Random Ordering

"While there are several ways to use the EHR to reduce variation, order sets are textbook examples. Order sets are just that, a set of orders that clinicians can employ with a single click."

COST

One often thinks of “quality” as simply being produced well and, as a result, there is an association with it being expensive. In healthcare, quality improvement is frequently associated with cost containment as well. Healthcare spending in the United States, as of 2019, reached $3.8 trillion, which is 17.7% of the entire gross domestic product (GDP). In light of these large costs to our society, it is imperative that healthcare stakeholders include costs when they strive to improve healthcare.

The EHR is important for delivering and documenting patient care, but the mandatory clinical decision support tools it provides can also be a rich source of cost savings and unrealized revenue. For example, interventions like alerts and defaults in order sets can provide clinicians with information around more cost-efficient choices in medications.

Commonly Referenced Terms

This is a very limited list into some commonly referenced terminology that you may stumble across in your quality improvement explorations.

SIX DIMENSIONS OF HEALTHCARE QUALITY

The Institute of Medicine released a report in 2001 entitled “Crossing the Quality Chasm.” This landmark paper outlined six aims that helped define what it means to deliver healthcare quality. The six dimensions are:

- Safe: “avoiding injuries to patients from the care that is intended to help them”

- Effective: “providing services based on scientific knowledge to all who could benefit and refraining from providing services to those not likely to benefit (avoiding underuse and overuse, respectively)”

- Patient-Centered: “providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions”

- Timely: “reducing waits and sometimes harmful delays for both those who receive and those who give care”

- Efficient: “avoiding waste, including waste of equipment, supplies, ideas, and energy”

- Equitable: “providing care that does not vary in quality because of personal characteristics such as gender, ethnicity, geographic location, and socioeconomic status”

THE TRIPLE AIM

When looking at the Six Dimensions of Healthcare Quality, you’ll notice the focus on direct care delivery. The IHI recognized that the health of a population doesn’t exist only within the walls of a hospital room or doctor’s office. The Triple Aim incorporates the health of communities that could include important factors like healthy food accessibility and affordable public transportation. The three aims are typically presented as a triangle with the following points:

- Improving the patient experience of care

- Improving the health of populations

- Reducing the per capita cost of healthcare

Landmark Reports

The following represent commonly referenced reports that helped transform society’s perspective on healthcare quality and patient safety.

TO ERR IS HUMAN: BUILDING A SAFER HEALTH SYSTEM (1999)

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) released this report and it helped open the eyes of many to the dangers of healthcare in the United States. The findings included the recognition that as many as 98,000 patients died every year as a result of medical errors. The analogy of a jumbo jet crashing each day was used to highlight the significance of these numbers. It’s no coincidence that the same year, the Agency for Health Care Policy and Research changed its name to Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

CROSSING THE QUALITY CHASM: A NEW HEALTH SYSTEM FOR THE 21ST CENTURY (2001)

The IOM followed up on “To Err is Human” two years later with a more comprehensive analysis of the state of healthcare in America. It is here that the authors outlined the Six Dimensions of Healthcare Quality through which stakeholders should try to improve the system. Importantly, the report recommends four levels when targeting the six dimensions:

- Patient experience

- Small unit of care delivery (“microsystem”)

- Organizations that encompass the microsystems

- Environment (e.g. legal, reimbursement, educational)

Expert Organizations

There are many organizations and institutions that are dedicated to healthcare quality improvement. However, these institutions play an integral role in the funding, education, and/or certification process.

AGENCY FOR HEALTHCARE RESEARCH AND QUALITY (AHRQ)

AHRQ is the principal federal agency that supports quality improvement research in the United States. Founded in 1989, AHRQ states its mission is “to produce evidence to make health care safer, higher quality, more accessible, equitable, and affordable, and to work within the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services and with other partners to make sure that the evidence is understood and used.” AHRQ had a total program funding level of $436 million in 2021. The largest portion of this budget, approximately $194 million, is dedicated to research on health costs, quality, and outcomes (HCQO).

INSTITUTE FOR HEALTHCARE IMPROVEMENT (IHI)

IHI is a non-profit organization that focuses on health quality. Founded in 1991, IHI states their mission is to “improve health and health care worldwide.” Unlike other organizations mentioned here, the IHI does not focus on the United States, but has regional efforts around the world. IHI’s website is a rich source for articles, methodologies, conference information, training programs, and more.

THE JOINT COMMISSION (TJC)

TJC is a non-profit organization that accredits healthcare organizations based on a set of national standards set by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Founded in 1951, TJC evaluates the practices of healthcare systems programs and certifies eligibility to participate in CMS’ reimbursement programs based on these national standards. TJC currently accredits more than 22,000 organizations within the United States. TJC will visit health systems to do checks and audits of practices and processes. Importantly, TJC’s website is a rich source of information for quality improvement and patient safety.

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR HEALTHCARE QUALITY (NAHQ)

NAHQ is a professional society dedicated to those interested in healthcare quality improvement. Founded in 1976, NAHQ’s mission is “to prepare a coordinated, competent workforce to lead and advance healthcare quality across the continuum of healthcare.” The organization sets a set of competencies required for healthcare quality specialists and administers a related Certified Professional in Healthcare Quality (CHPQ) exam. NAHQ additionally holds its annual NAHQ NEXT conference alongside other events and educational opportunities.

Journals and Publications

It’s important to recognize that there are great pieces published in a variety of settings. The following is a selection of some publications that principally focus on quality improvement and patient safety.

BMJ QUALITY & SAFETY

A peer-reviewed journal within the umbrella of the BMJ Publishing Group. The monthly publication seeks original material on “the science of improvement, debate, and new thinking on improving the quality of healthcare.”

JOURNAL FOR HEALTHCARE QUALITY

The official peer-reviewed journal of the National Association for Healthcare Quality is published every two months. The journal states it is a “professional forum that continuously advances healthcare quality practice in diverse and changing environments, and is the first choice for creative and scientific solutions in the pursuit of healthcare quality.”

THE JOINT COMMISSION JOURNAL ON QUALITY AND PATIENT SAFETY

The official peer-reviewed journal of The Joint Commission. The monthly publication encourages submissions on the “development, adaptation, and/or implementation of innovative thinking, strategies, and practices in improving quality and safety in health care.”

PHRASE'S EXPERTISE

Improved Adherence to Hepatitis C Screening Guidelines →

Responding to COVID-19: Reducing Documentation →

References

1. “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.” National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25057539/.

2. Monsen CB, Liao JM, Gaster B, Flynn KJ, Payne TH. “The Effect of Medication Cost Transparency Alerts on Prescriber Behavior.” Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association : JAMIA, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31321427/.

3. Kohn LT, Corrigan JM, Donaldson MS. “To Err Is Human: Building a Safer Health System.” National Center for Biotechnology Information, U.S. National Library of Medicine, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25077248/.

.svg)

.svg)